by Steve McAlpin

Receipt of the painting took over a year to be acknowledged by the White House Gift Office due to the Anthrax scare of the early 2000’s. It’s homemade ¼” plywood case was pulled together with drywall screws and bound in Army-green “Hundred-mile-an-hour (Duct) Tape. A black Sharpie was used to inscribe its destination: 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C.

I served in an unprecedented position during America’s first year in Afghanistan. The sprawling complex known as Bagram Airfield was home to about 2,000 Special Operations and support soldiers. I was among those SpecOps soldiers, but not the type that often comes to mind when the term is used. I was an Army Civil Affairs Officer, a Captain with a Bachelor’s in History Education and a Master’s Degree in Special Education. My assignment was to serve as the Base S-5 – the senior liaison between the Coalition Forces, and Afghan military, political, and civilian communities.

As SpecOps soldiers, we were authorized to implement “relaxed grooming standards,” a rare military practice whereby soldiers could wear civilian clothing, and did not have shave or get haircuts. This practice had numerous benefits including blending in with local Afghans which would increase our force protection and thus save Coalition lives.

As I surveyed the base, a two-story building complex about a half-mile from the main gate piqued my interest. I was told it was the remains of the local high school. So, as part of my official duty, I introduced myself to the school principal, Ghulam Ghus, and his all-male staff of about 15 teachers. To a man, they were delighted that the Americans had come. Many of the school staff had been killed by the Taliban or had fled to Pakistan to protect themselves and their families.

When I mentioned that I was a teacher back in the United States, they begged me to begin an English Language Program at the school. Classes were beginning in during the second week of March, 2002, which gave me only two weeks to gather school materials, recruit “volunteer” teachers from the soldiers on base, and particularly, to gain permission to teach at the school. I knew that without the proper permission, we would be doomed to failure.

It seemed that everyone at Bagram worked at least 18 hour per day. There was SO much to do, and nobody really needed anything extra on their plate. However, it seemed that everywhere we turned, there was an Afghan with an almost embarrassingly little amount of world knowledge. When I proposed the teaching idea to my direct boss, base commander Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Edward Dorman III, his reaction stunned me and brought a huge smile to my face.

“That’s a great idea, Steve. Sure…as long as I can teach a class too!”

I was overwhelmed with optimism, so proceeded to gather as many pencils, pens, crayons, markers and notebooks as I could. “Blackboards” consisted of a simple rectangular coat of black enamel painted on the front wall of each room. White chalk was used on the boards, but was in very short supply. So LTC Dorman and I signed for a few white dry-erase boards to simplify matters. Further permission to teach was granted from the School District’s Superintendent and finally, from the Assistant Minister of Education in the Capital city of Kabul. We were allowed to teach three, one-hour classes per week.

Along with being my biggest proponent of the teaching program, LTC Dorman supported me when I mentioned that we needed to build some desks and benches for the students who were otherwise sitting on hard concrete floors.

“Steve, get with the 92nd Engineers and tell them what you want to do. Then head over to Contracting and fill out a request for supplies.” That sounded simple enough.

The Engineers were very excited about the project and readily agreed to build over 200 desks and benches for the school. However, the Contracting officer, Major Stevenson, was not quite so agreeable. “Captain McAlpin, we’re not building anything for Afghans! Our supplies are for Americans only!” I was quickly ushered out of the office.

After our daily Battle Update Brief with Dorman the following day, I mentioned to him that Contracting refused to give us any supplies for the school. He immediately turned on a heel and said: “Major Stevenson, a word?”

Stevenson quickly made the three steps to the commander.

“Major Stevenson, I don’t care if you have to tear up ‘bleeping’ tent floors. We’re going to build desks and benches for the school. Understood?”

“Ye, yes sir. I’ll authorize the supplies.” Dorman glanced back at me with a swift Cheshire smile. “Gosh.” I said to myself, “I love this guy!”

With the desks and benches built, the school season could begin with a most positive contribution by the Americans.

Wearing civilian clothes with my M-9 Pistol tucked into the back of my pants, we began teaching the very basics of conversational English to 11th Grade students between 17 and 29 years old. I was as nervous as I had ever been. We were about to be the first people to teach formal English classes in Afghanistan in the last 23 years.

I knew there was a great need for knowledge, but the first day of teaching really opened my eyes as to the depth of that knowledge. Through my translator, Jawad, I introduced myself:

“Salaam wa lakum. Nomay Steve ast ee ma malim ostem (from New York).”

“May God be with you. My name is Steve and I am a teacher from New York.”

The mostly-bearded students seemed impressed with my Dari as smiles came to their lips.

That was all the Dari I had, so I spoke through Jawad for the remainder of the class.

“Does anyone know where New York is?” Only one of the 18 students raised his hand.

“How about the United States? Does anyone know where that country is?” Only two more hands went up.

“North America? How about North America?” One more hand rose.

I leaned over to Jawad and told him: “Jawad, we need to bring in a world map tomorrow.”

“Oh no sir” he replied, “we need a globe. A map will make them think the world is flat!”

I knew at that moment just how important even a basic education was to these young men and women. That afternoon, I searched the myriad of stores off-base for hours, but could only find a 3” diameter globe from which to teach. It was the first globe that many of them had ever seen.

As the days and weeks passed, I was able to recruit 17 American and British “teachers.” During that period, there were no enemy attacks on Bagram Airbase. We believed that it was because we involved the entire surrounding community in the school program. Teachers and students would travel from as far away as two hours to participate in our program.

Then, Big Army moved in. The parent unit of the 10th Mountain Division, which was the initial combat division into Afghanistan, was the XVIII Airborne Corps. It is customary to welcome a higher-echelon force through a series of briefings to bring them up to speed with the situation on the ground.

I briefed the Corps’ Senior Civil Affairs Officer, Colonel (COL) Kassem Saleh, on the Civil-Military activities going on in and around the base. When I got to the teaching program, the Colonel stated:

“Teaching English to Afghans is stupid. You will end that program tomorrow!” I was bewildered by the dismissiveness of this single program. I tactfully tried to outline the benefits of the program not only to the Afghans, but to the entire base and the Coalition Forces therein.

Saleh would hear none of it. He demanded that we stop teaching immediately. I was crushed.

Later that day, I drove over to the school with another translator, a female Afghan-American named Shakiba. We had only expected the principal to be there, but he happened to be having a staff meeting which included the rest of the Afghan teachers.

Everyone stood when we entered the room. Ghus insisted that I sit in his battered chair while he leaned against a wall.

Through Shakiba, I told them that I had some very sad news to report.

“We have been directed to end our participation in the teaching process at once.” I could feel myself begin to shudder and burst out in tears. I didn’t want that to happen in front of these great men, but I couldn’t help myself. As I covered my face, the group gathered around and hugged me tightly. After a couple minutes, I broke free and told them that I will continue to fight for them.

“Like General Ahmed Shah Masseud (the Northern Alliance Commander assassinated by al Qaida on 9/9/2001), I will not give up. I will continue to fight for you and the students.”

Fighting this order was futile, and within a couple weeks, I found myself and my right-hand man, SFC Juan Morales being transferred to a Safe House in Kabul where senior officers could keep a closer eye on my activities. Big Army had moved into town, turning a perfectly unconventional war into the conventional disaster it remains today.

There were some advantages to being stationed at the Safe House. Among them, freedom to travel up to four hours away to assess schools, governmental buildings, medical clinics, and business reconstruction projects. We would often suggest that we were willing to dig wells for the villagers of some areas – particularly the ones that agreed to teach females.

The Safe House also gave me time to paint. Though color-blind, I was so upset by the decision to end the teaching program that I sent home for my acrylics and brushes. I needed to make a splash over this issue because I firmly believed that we were doing the right thing for the Afghan people. As Thomas Jefferson said, “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.”

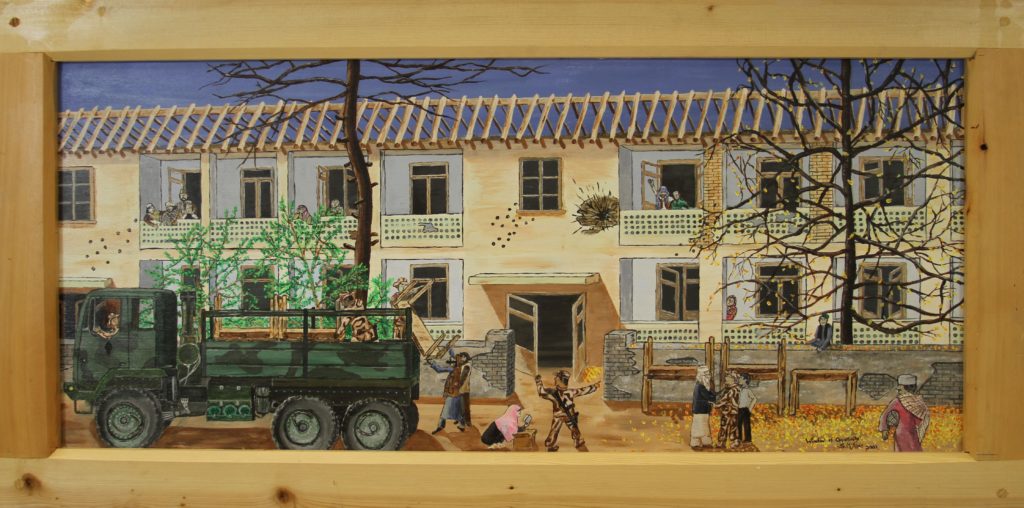

The following denotes some of the symbolism that can be seen in this painting:

• There are five American Soldiers depicted that represent the five points of a star. Amazing to me was the ethnic diversity of the construction Engineers, and my 17 teacher-volunteers – a broad swath of our American Fabric.

• There are a total of 21 people in the painting. They represent a 21-gun salute to the fallen service members who died during Operation Enduring Freedom.

• The large tree to the center-left has its lower branches shorn to provide a better field of fire to the defenders of the structure. While the school was a fighting position, the dead tree represents the death of the old Afghanistan.

• The tree on the right with the yellow leaves represents life, and the optimistic beginning of a new Afghanistan. This is complimented by two fresh saplings with green leaves. They guarantee the viewer that positive change will occur in Afghanistan.

• The man holding a volleyball in the bottom-right corner of the work represents the former leaders of the country – the Taliban. This man looks on with disgust, wondering if and when he can reassert his oppressive influence.

• There are four men in the upper left of the painting that represent the older-than-usual student population. Stifled by constant war, the 11th grade boys I taught were between 17 and 29 years old. All students were taught by males…until we got there.

• Two female students look down from the balcony with little optimism. Education had been discouraged throughout their lives and they wonder if they will be allowed to attend school equally with boys.

• Sitting on the wall is a young man looking forward to sitting at his new desk instead of the cold concrete floors to which they had become accustomed.

• Hiding behind one of the columns on the first floor stands a young woman, still afraid of this “education” thing that might just be a trap of some sort.

• There is a young woman stooped over a box at the bottom-center of the painting. She is opening a book for the first time in her life. The box of books was provided through the Humanitarian Assistance Program (HAP) to cut through reams of government red-tape. We doubt that she can read a single word…yet!

• An American Officer (me) shakes hands and speaks with an overwhelmed school principal, assisted by his Afghan translator. Another American, a Non-Commissioned Officer (SFC Morales) is seen organizing the delivery and directing two Afghan teachers where to place the newly made desks and benches. There are two more American soldiers unloading from the back of the truck.

• The driver of the American vehicle is sporting the unit patch of the 92nd Engineer Battalion. Below his arm is the logo of the unit, “Black Diamonds.”

• The building is constructed with alternating windows and doors. All of the doors are open to the outside balcony, allowing for free movement of people. All of the windows are closed, as is much of Afghan society – especially to women.

• The corrugated tin that made up the roof of the school was gradually removed by needy civilians who used it for shelter as their homes were being destroyed by years of constant war.

• Finally, the frame of this painting is an actual window frame purchased for $7.00 from a carpenter at the Teacher’s Training College in Kabul. The college was completely destroyed and became a major project in the American effort to get the country back on its feet. Thus the title: “Window of Opportunity.”

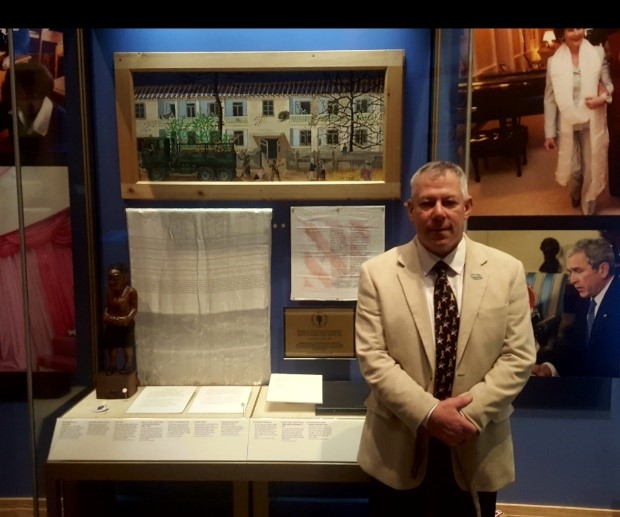

In an e-mail message from June, 2013, I received word that my painting was indeed seen by the President and Mrs. Bush and was actually on display at the Presidential Library and Museum.

The message read:

“…this e-mail is to confirm that your painting “Window of Opportunity” is currently on public display at the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum. It resides in a display case featuring various humanitarian and human rights outreach efforts made during the President’s time in office. It is featured prominently within its case, placed on top and center above a shawl given to the President by the Dali Lama and a handmade handkerchief with a poem by Cuban human rights advocate, Oscar Biscet.”

I arranged to meet with one of my dearest Army friends who resides near Ft. Bliss, Texas, to take a trip to the Museum and see it firsthand. When we arrived, we met with the gentleman who wrote the above e-mail message. He led us to the Humanitarian section of the museum and there it was, exactly as described. I simply couldn’t believe it was there.

As I began to explain the symbolism within the painting to my friends, a small group gathered around me. Soon, the Museum director, Mr. Alan C. Lowe blended into the crowd.

“Did you really paint this picture?” he asked.

“Yes sir. I can’t believe that it’s on display!”

“Well we are very proud to have it among our collection. Hardly any of the contributors actually come to the Museum to see their gift. Let me give you some surprising statistics.”

My small entourage stood with our mouths open as Mr. Lowe continued.

“During the President’s time in Office, he received about 50,000 gifts from around the world. Of those, between 3,000 and 5,000 were paintings. We decided that only 300 total artifacts would make up the original display, of those only 5 of the 300 items are paintings. You are in very good company.”

I simply couldn’t believe my good fortune. I notified LTC (now a 2-star General) Dorman of the painting’s status. He was humbly proud of the effort I made and his not-so-small contribution to this history-making piece of American military art.